It had it all: the initial incident and then the cover-up. The involvement of political influence at the highest level. Disappearing evidence and prosecution of lower level operatives. It was not Watergate in 1972, it was Buttergate in 1975, and Kemptville found itself, not for the last time, the object of national attention and media coverage. In a famous novel and movie, “Whiskey Galore”, a Scottish village takes advantage of a shipwreck to relieve the stricken ship of its cargo of whiskey. In Kemptville, perhaps typically, it wasn’t whiskey, it was over 7,000 pounds of butter!

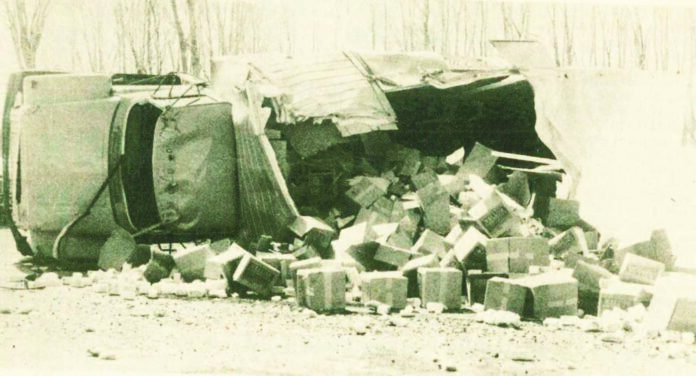

It all started on April 9, 1975 at the junction of River Road and what was then Highway 16. An Eganville Creamery truck, containing 379 cases of butter, was heading south on Highway 16 when it was hit by another vehicle. It was quite a collision and both vehicles were right-offs. The Eganville truck was tossed on to its side and the cargo of butter was scattered over the road. By the time the site had been cleared and people from Eganville arrived to collect their 19,000 pounds of butter, it was discovered that 160 cases of it were missing, about 7,425 pounds of the stuff.

Kemptville Police Chief, Steve Kinnaird began an investigation into the disappearance, and soon learned that two trucks from the Kemptville Truck Centre had arrived and removed the missing butter, valued at almost $8,000. That is almost $40,000 in today’s dollars. This was not a minor issue, especially when Chief Kinnaird discovered that the stolen merchandise had been quickly distributed among about 27 local residents. It seemed half the town were in the deal. To make his position much more uncomfortable, one of those 27 residents was the Mayor of Kemptville, Ken Seymour.

By July 3, Chief Kinnaird felt that the political pressure being brought to bear on the investigation required that he find some extra help from outside the town. Crown Attorney John Van Plew, from Brockville, had been gathering evidence for a trial, and recognised the delicate position Chief Kinnaird was in. He contacted the Criminal Investigation department of the Ontario Provincial Police in Toronto, and Detective Inspector M. K. McMaster arrived to join in the case.

By September, the 27 individuals who had received part of the stolen butter had been identified, and three men had been arrested and charged. The case came to trial in April, 1976 in Brockville, with Judge Mossman Dubrule presiding. Two of those charged were found not guilty and the charges against the third man were therefore dropped. But Judge Dubrule was quite scathing in his judgment. Although he found little solid evidence upon which to convict the accused, he labelled the case “Buttergate”, and said that it bore all the earmarks of a scandal, with suspicion of wrongdoing by influential town residents.

During the police investigation into the theft, about 600 pounds of butter had been recovered after Chief Kinnaird and Inspector McMaster had warned the 27 that they would be prosecuted if it was not handed in. That still left more than 6,700 pounds missing, and it was said that most of the remainder had been fed to pigs by one of the 27.

The matter was then raised in the Ontario Legislature by Ottawa East MPP Albert Roy, who wanted the Attorney General, Roy McMurtry to investigate any unfair political influence in prosecuting the case. He wanted to know why only three individuals had been charged, when there were 27 people known to have been in possession of the stolen butter, including Mayor Seymour. Had the mayor brought undue influence to bear to curtail the inquiries? When interviewed by Inspector McMaster at the time, Mayor Seymour had admitted coming into possession of 200 pounds of the butter, but claimed that the butter had been placed in his car and on his doorstep, without his knowledge. He had then given the butter away to local residents, according to an article in the Ottawa Journal.

Crown Attorney Van Plew was then instructed to make a report to the Attorney General on the matter. A more formal legislative committee was set up to look into the allegations that the Mayor and others had been allowed to avoid prosecution because of their position in the town, and this would, in turn, lead to even more controversy when the OPP and the Crown Attorney’s Office traded accusations about who, precisely, made the decision not to charge the mayor and the rest of the 27 known accomplices. That part of the fun and games will be discussed in a future article.