Fred Schueler and Aleta Karstad remember the ice storm twenty years ago all too well. They were living in their current home in Bishops Mills and survived the fourteen days without power thanks to their wood-burning stove, outside freezer and a bathtub full of water (which they had filled before the power went out). They watched and participated as the community came together to support each other in the extreme weather event in Eastern Ontario that rocked the beginning of 1998.

As naturalists and observers, Fred and Aleta used the ice storm as an opportunity to gather information about how the ice storm affected the flora, fauna and habitats of the area. “I measured the excess diameter of the twigs caused by the ice,” Fred remembers. “There was 50 mm of excess diameter on everything.” Throughout the duration of the storm, Fred noted that the temperature remained roughly the same, between -2 and +0.5. When it ended the temperature plummeted into a deep freeze, further solidifying the ice that had built up on the trees, bushes and ground.

While in some cases the excess ice made a bush more structurally sound, when it came to some trees the ice weighed them down and caused them to snap. “In the wind the poplar trees would break in half,” Aleta remembers. “It sounded like artillery in the distance.”

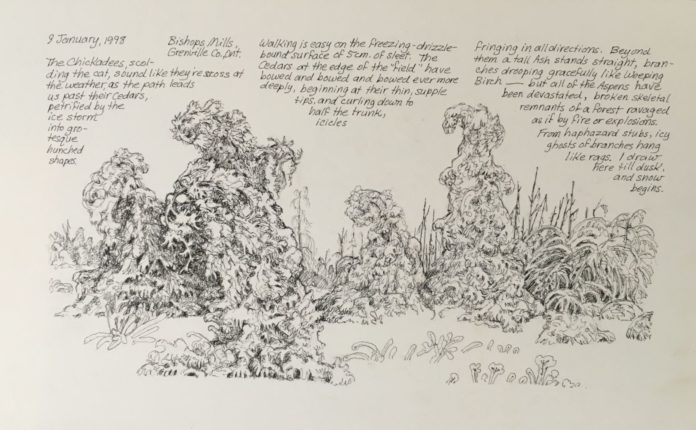

Forests were ravaged during the ice storm with trees falling down and bent in all sorts of different directions. “It looked like photographs from World War 1,” Fred says.

Fred and fellow researchers David and Carolyn Seburn were employed by the Ministry of Natural Resources to look at how the extra layer of ice may have affected small mammal populations in Eastern Ontario. The trio sampled 90 different places within the area affected by the ice storm which were evenly divided between four habitats: old fields, fence rows, coniferous forests and deciduous forests. They found that the average thickness of the ice lens was 8-9 cm thick and this did not differ between the different habitats.

Fred and his colleagues found that it was hard to tell how most small mammals, including mice, shrews and moles were affected by the storm. However, they found that voles, who make tunnels under the snow to move around during the winter, were restricted in terms of where they could go because of the ice. They were also unable to dig their ventilation holes up to the surface to allow them to breathe under the snow. Because of this, their report speculated that the ice storm may have added to the already high rate of death for voles over the winter.

On her own accord Aleta says she observed some activity among mice populations near their home. From their under-snow tunnels they gravitated towards where they could smell fresh air around the trees. “I could hear them squeaking at the base of the trees under the snow,” she says. “I definitely witnessed social distress among the mice.”

Larger animals like deer and rabbits seemed to do quite well during the storm, taking shelter in their usual winter habitats. The rabbits ate fallen buds and deer were able to keep munching on the conifer trees that make up the forests where they winter. Wild turkeys were actually drawn closer to the human population as they relied on people’s bird feeders for nourishment. “The ice storm triggered the turkeys to be less afraid of people,” Fred says.

Any animal population loss caused by the ice storm has most likely been repopulated and no deer or rabbit is likely to remember those frigid two weeks. However, if you look at some of the trees in this area, you can still see where they were warped and damaged by the thick ice that once coated their branches. A reminder of a time in the area’s history that many remember as one of the more significant weather events of their lifetime.