When the delegates returned home from the Quebec Conference in late 1864, they must have felt that they were on the brink of achieving a tremendous new chapter in the history of British North America. With the 72 Resolutions composed, and a new scheme for the union of all the British American provinces agreed upon in its essentials, Confederation must have seemed mere months away. Why, then, did it take another two years to bring the Ship of State to safe harbour?

The reception received by the delegates must have seemed like a shower of cold water, waking them to the fact that they had been living in a bubble for almost two months. In the cocoon of conference rooms and dinners, they had failed to realise the depth of opposition to the very concept of Confederation which existed in their home provinces. Even in the Canadas, where the Great Coalition had first designed the project, parties on both sides of the Ottawa River were ready to find fault with the scheme.

The Rouges party in Lower Canada [Quebec] raised the issue of French Canadian nationalism and warned that the new federal structure of Confederation would leave the francophone community in a minority within the new nation. The Grits in Upper Canada warned that the people in that section would end up paying for the promised Intercolonial Railway and other infrastructure commitments, without receiving any of the benefits which would accrue to the Maritimes. In future years, these two groups would join with others to form the new Liberal Party of Canada; but in 1864-65 they could not stop the Legislative Assembly from debating and approving the 72 Resolutions and the coming of Confederation.

It was far more serious in the Lower Provinces. Even during the Charlottetown and Quebec Conferences, it was clear that Newfoundland was not seriously interested in joining the Confederation process. Isolated geographically, and economically looking to New England and Britain, a union of British America held little appeal for them. The same was even more true, perhaps, in Prince Edward Island. The original conference had only taken place in Charlottetown because the Islanders refused to go anywhere else, such was their lack of enthusiasm for the scheme. Seeing little of value for them in Confederation, they failed to even raise the Resolution in their Assembly. It died a quiet death on PEI, for the time being at least.

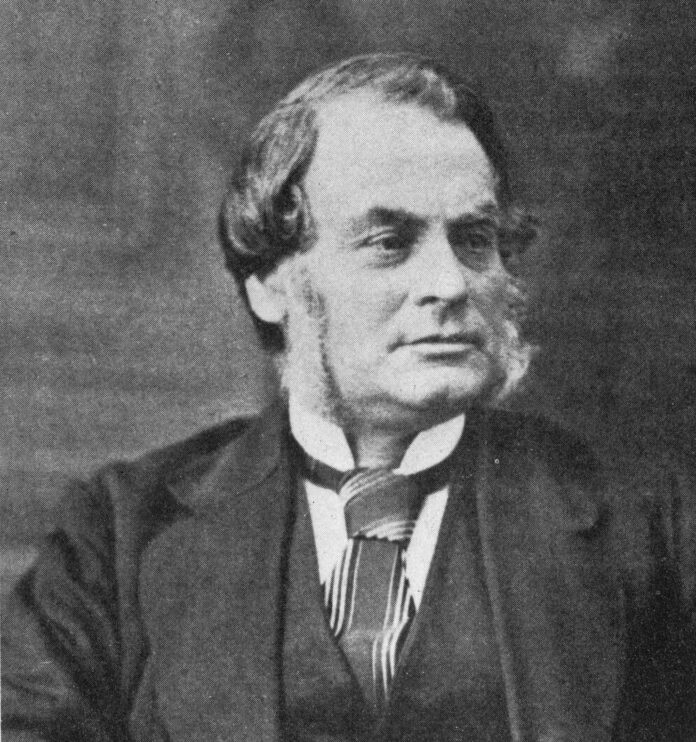

Far more important was the response of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Charles Tupper returned to Halifax to find a major obstacle to Confederation in the person of Joseph Howe, his most powerful political rival. Howe had not been part of the process during that summer and early autumn, and had tapped into a strong feeling of provincial patriotism in the province. Nova Scotians prided themselves on having an important link to the British Empire, a strategic outpost of naval power, and a tradition of independence, weak ties to Canada and economic and social bonds with New England. Tupper decided it would only court defeat to introduce the 72 Resolutions in the Assembly and chose to wait upon developments elsewhere.

Elsewhere, in this case, meant New Brunswick, the one province absolutely essential for the Confederation scheme. Without that geographical connection between the Canadas and the Atlantic provinces, Confederation was impossible. It was through New Brunswick that the Intercolonial would run to tie the new country together, and it was in New Brunwswick that the winter port on the Atlantic would provide a lifeline to the nation to the west. New Brunswick was critical, and New Brunswick was far more opposed to Confederation, it seemed, than Samuel Tilley expected as he called an election for early 1865.

Confederation was the main issue, and this would be the first time that voters anywhere in British North America would have the chance to speak on the subject.

They spoke loudly, defeating Tilley’s government by a wide margin of seats – Tilley himself was among the defeated – and placing an apparently insurmountable obstacle in the road to Confederation. After all the excitement and hope of 1864, and the almost unbelievable speed with which politicians from all over British America had collaborated on bringing the scheme to that point, by March of 1865 it seemed the entire edifice had collapsed in irretrievable ruin. The way in which Confederation rose from the ashes of this defeat would be beyond the imagination of the most gifted writers of fiction. The story of Confederation was about to see its most dramatic chapter.